Isn’t it strange that you could travel back in time to a point in the Earth’s history when the very atmosphere could poison you?

Of course there are the long years before life on Earth had evolved and there was no oxygen at all. But there have also been at least one period of high oxygen levels when insects could grow to gargantuan size and several periods of extremely high carbon dioxide levels.

In a post on The Atlantic site by science writer Peter Brannen called “Burning Fossil Fuels Almost Ended All Life on Earth,” Brannen vividly details what it would be like to visit one such era, the Permian-Triassic boundary around 250 million years ago:

You walk down to the shoreline and take a few steps into the lapping waters, drawn toward the enveloping gloom. The seawater is almost painfully hot. There’s nothing alive under the waves. There doesn’t seem to be anything alive anywhere really. You squint and marvel at the growing terror on the horizon. You’ve seen billowing thunderclouds before, but this panoramic tempest seems to tower into eternity. Wild hot winds begin to whip in all directions. You find it difficult to breathe. Slowly baking, you know should head back to the temporary safety of the ship, but you linger here all alone on the dimming coast, transfixed by the blossoming apocalypse just over the Earth’s curve. A putrid odor begins to ride in on the swirling winds and, as you finally turn back in a panic, you pass out. Before long, this doomsday storm makes landfall, and what meager life clings to this country is stamped out for millions of years.

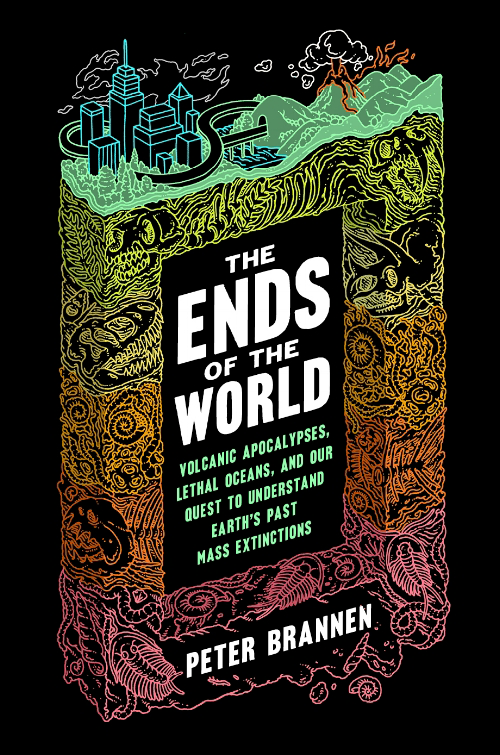

Because of this great writing, I bought Brannen’s debut book, The Ends of the World, which came out this past June. It’s a clever, often times beautifully written account of the past five mass extinctions in the deep past of the Earth, when almost all complex species were destroyed by overwhelming geological and astronomical forces. Like the best science writing (I would compare this book favorably to Peter Ward’s Gorgon), Brannen makes the story of scientific discovery an adventure, chronicling contrasting theories of events in deep time through road trips and engaging discussions with scientists. Unlike the common conception of asteroid and comet strikes, geologists and paleoclimatologists now hypothesize that these extinctions were driven by sudden changes in the concentration of carbon dixoide in the atmosphere. One of those changes was a drop, possibly caused by the evolution of trees, which drew down CO2 levels and summoned glaciers. But most of those changes were spikes in CO2 caused by continent-sized volcanic eruptions, huge boils in the Earth’s surface that broke open to bake the land and acidify the seas.

Cover by Eric Nyquist.

This new understanding of the past is extremely relevant to today because we’re pumping carbon dioxide into the atmosphere at a faster rate than those ancient lava flows. Like many, I was scared and panicked about David Wallace-Wells’ article on the worst-case scenario for climate change in New York Magazine. One aspect to many of the projections he collects in the post is that most of them stop, somewhat arbitrarily, at the year 2100. But as Peter Brannen and other science writers (such as Curt Stager in Deep Future, which I discussed in this post) warn us, our actions now will not only affect the next century but millennia to come. That’s why the perspective of deep time is so important to the discussion of climate change and yet simultaneously makes it too abstract for it to become a pressing policy issue for the majority. Maybe some immediate animal fear of being baked from the inside, or losing cognitive function from too much CO2, like Wallace-Wells caused in me, can spur us into action.

One positive fact that I got from Brannen’s book is that, despite many claims to the contrary, we are not (yet) in the midst of the sixth mass extinction in Earth’s history. Even if you add in all the megafauna extinctions, such as the loss of the charismatic giant ground sloths who ate avocados and dug out elaborate tunnel systems in South America, the world has lost only 1% of its species since we evolved. In the five mass extinctions in Earth’s history, the world lost over 75% of its species. There’s still time for us to implement sensible climate change mitigation policies and preserve our world, civilization, and culture for the centuries to come.

If you’re like me and need a chaser of hope for a shot of doom, read this post by futurist Alex Steffen on how climate action is imminent and check out this chat on Vox about Drawdown, Paul Hawken’s project to explore practical climate change solutions that use existing tech.